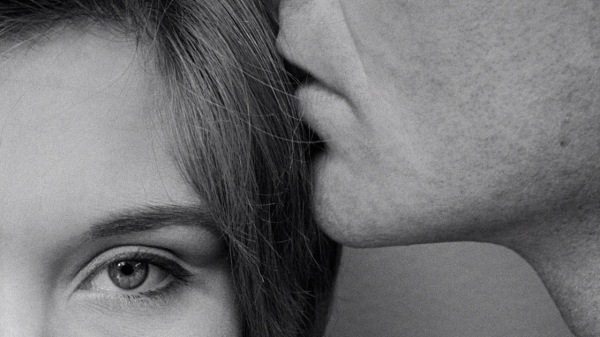

The subtitle for Jean-Luc Godard’s “A Married Woman” is “Fragments of a Film Shot in 1964, in Black and White,” which is true in more ways than one. In the early scenes, and repeatedly throughout the film, all we see on the screen is pieces of two lovers’ bodies – hands reaching for each other, lips whispering into an ear, a naked torso.

The effect is erotic — Godard skirts the edge of censor-worrying nudity without slipping over — but unsettling, as we never get a clear full-length shot of these two people together. After the free-wheeling camerawork of “Breathless” and “Band of Outsiders,” the rigorous formality of these shots feels constrained. The people seem pinned inside the frame like specimens, with Godard (and us) watching their lovemaking from an almost clinic distance.

“A Married Woman,” which was released on Blu-ray this week from Cohen Media Group, was the first of Godard’s so-called “sociological” movies looking at modern society. And, as critic Antonio de Baecque says in one of the interviews on the disc, it was made on something of a dare for the French New Wave filmmaker.

He had brought “Band of Outsiders” to Cannes in May 1964 to much acclaim, and the director of the Venice Film Festival approached him and expressed a desire to have a new Godard premiere at his festival. Godard agreed, cheekily but perhaps rashly, that he’d have a new film ready to premiere at that year’s Venice Film Festival, in five months.

Having made the commitment, Godard scrambled to film “A Married Woman” over the summer. The story that took shape was one of the sexual revolution, of a bored housewife named Charlotte (Macha Meril) who has an affair, gets pregnant, and then has to decide which man she will stay with. Familiar story, but Godard wasn’t interested in melodrama, instead hiring Meril largely for her looks (she says in a wonderful present-day interview on the disc that she felt like an “animal” or a “statue” on screen) and turning her plight into a disjointed collage of images and enigmatic voiceovers.

The joke turned out to be somewhat on Godard – he thought he had hired a raw ingénue in Meril that he could mold to suit his vision (he even picked out her wardrobe himself). But the Russian-born Meril was an experienced actress who had studied at the Actors Studio, and although she looks beautiful on screen, it’s also a deeply felt, quietly tragic performance.

While the scenes with the wife and her lover are filmed in those fragments, the scenes with her husband are long and naturalistic; this is not the wife’s first affair, and the husband had even hired a detective to follow her. The camera is often placed outside the apartment, as if on the balcony, as we watch through windows as characters go in and out of rooms. Once again, they are under glass, trapped in the routines of a bourgeois couple.

Godard was very interested in the effect that a sexualized consumer culture had on women, and one of the most famous scenes in the film features Charlotte leafing through page after page of lingerie ads, a barrage of cleavage and come-hither looks. (Godard was conveying the message of feminist media documentaries like “Miss Representation” decades before them.) The sequence ends with a great joke, as Charlotte is shown sitting right in front of a billboard of a woman, her head looking tiny between the gargantuan swells of her breasts. It elicits a laugh, but it’s also a telling image, of how real women are dwarfed by the presence of these fantasy women.

“A Married Woman” ends rather desultorily, and the last shot of the film is a reverse of the first shot, so the hands that were once reaching towards one another are now pulling away. What began almost as a stunt for Godard ends up being something of a masterpiece, and the start of a new period in his long filmmaking career.